While there have been several attempts at providing alternatives, modern decentralized storage networks (DSNs) often fall short on basic aspects like having strong durability guarantees, being efficient to operate, or providing scalable proofs of storage. This in turn leads to solutions that are either: i) not useful, as they can lose data; ii) not friendly to decentralization, as they require specialized or expensive hardware, or; iii) economically unfeasible, as they burden providers with too many costs beyond those of the storage hardware itself.

In this paper, we introduce Codex, a novel Erasure Coded Decentralized Storage Network that attempts to tackle those issues. Codex leverages erasure coding as part of both redundancy and storage proofs, coupling it with zero-knowledge proofs and lazy repair to achieve tunable durability guarantees while being modest on hardware and energy requirements. Central to Codex is the concept of the Decentralized Durability Engine (DDE), a framework we formalize to systematically address data redundancy, remote auditing, repair, incentives, and data dispersal in decentralized storage systems.

We describe the architecture and mechanisms of Codex, including its marketplace and proof systems, and provide a preliminary reliability analysis using a Continuous Time Markov-Chain (CTMC) model to evaluate durability guarantees. Codex represents a step toward creating a decentralized, resilient, and economically viable storage layer critical for the broader decentralized ecosystem.

1. Introduction

Data production has been growing at an astounding pace, with significant implications. Data is a critical asset for businesses, driving decision-making, strategic planning, and innovation. Individuals increasingly intertwine their physical lives with the digital world, meticulously documenting every aspect of their lives, taking pictures and videos, sharing their views and perspectives on current events, using digital means for communication and artistic expression, etc. Digital personas have become as important as their physical counterparts, and this tendency is only increasing.

Yet, the current trend towards centralization on the web has led to a situation where users have little to no control over their personal data and how it is used. Large corporations collect, analyze, and monetize user data, often without consent or transparency. This lack of privacy leaves individuals vulnerable to targeted advertising, profiling, surveillance, and potential misuse of their personal information.

Moreover, the concentration of data and power in the hands of a few centralized entities creates a significant risk of censorship: platforms can unilaterally decide to remove, modify, or suppress content that they deem undesirable, effectively limiting users’ freedom of expression and access to information. This power imbalance undermines the open and democratic nature of the internet, creating echo chambers and curtailing the free flow of ideas.

Another undesirable aspect of centralization is economical: as bigtech dominance in this space evolves to an oligopoly, all revenues flow into the hands of a selected few, while the barrier to entry becomes higher and higher.

To address these issues, there is a growing need for decentralized technologies. Decentralized technologies enable users to: i) own and control their data by providing secure and transparent mechanisms for data storage and sharing, and ii) participate in the storage economy as providers, allowing individuals and organizations to take their share of revenues. Users can choose to selectively share their data with trusted parties, retain the ability to revoke access when necessary, and monetize their data and their hardware if they so desire. This paradigm shift towards user-centric data and infrastructure ownership has the potential to create a more equitable and transparent digital ecosystem.

Despite their potential benefits, however, the lack of efficient and reliable decentralized storage leaves a key gap that needs to be addressed before any notion of a decentralized technology stack can be seriously contemplated.

In response to these challenges, we introduce Codex: a novel Erasure Coded Decentralized Storage Network which relies on erasure coding for redundancy and efficient proofs of storage. This method provides unparalleled reliability and allows for the storage of large datasets, larger than any single node in the network, in a durable and secure fashion. Our compact and efficient proofs of storage can detect and prevent catastrophic data loss with great accuracy, while incurring relatively modest hardware and electricity requirements -- two preconditions for achieving true decentralization. In addition, we introduce and formalize in this paper the notion of durability in decentralized storage networks through a new concept we call the Decentralized Durability Engine (DDE).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss the context on which Codex is built (Sec. 2) by expanding on the issues of centralized cloud storage, and providing background on previous takes at decentralized alternatives -- namely, p2p networks, blockchains, and DSNs. Then, we introduce the conceptual framework that underpins Codex in Sec. 3 -- the Decentralized Durability Engine (DDE) -- followed by a more detailed descriptions of the mechanisms behind Codex and how it materializes as a DDE in Sec. 4. Sec. 5 then presents a preliminary reliability analysis, which places Codex's storage parameters alongside more formal durability guarantees. Finally, Sec. 6 provides conclusions and ongoing work.

2. Background and Context

Codex aims at being a useful and decentralized alternative to centralized storage. In this section, we discuss the context in which this needs arises, as well as why past and current approaches to building and reasoning about decentralized storage were incomplete. This will set the stage for our introduction of the Decentralized Durability Engine -- our approach to reasoning about decentralized storage -- in Sec. 3.

2.1. Centralized Cloud Storage

Over the past two decades, centralized cloud storage has become the de facto approach for storage services on the internet for both individuals and companies alike. Indeed, recent research places the percentage of businesses that rely on at least one cloud provider at

The appeal is clear: scalable, easy-to-use elastic storage and networking coupled with a flexible pay-as-you-go model and a strong focus on durability[2] translating to dependable infrastructure that is available immediately and at the exact scale required.

Centralization, however, carries a long list of downsides, most of them due to having a single actor in control of the whole system. This effectively puts users at the mercy of the controlling actor's commercial interests, which may and often will not coincide with the user's interests on how their data gets used, as well as their ability to stay afloat in the face of natural, political, or economical adversity. Government intervention and censorship are also important sources of concern[3]. Larger organizations are acutely aware of these risks, with

The final downside is economical: since very few companies can currently provide such services at the scale and quality required, the billions in customer spending gets funneled into the pockets of a handful of individuals. Oligopolies such as these can derail into an uncompetitive market which finds its equilibrium at a price point which is not necessarily in the best interest of end-users[5].

2.2. Decentralized Alternatives: Past and Present

Given the downsides of centralized cloud storage, it is natural to wonder if there could be alternatives, and indeed those have been extensively researched since the early 2000's. We will not attempt to cover that entire space here, and will instead focus on what we consider to be the three main technological breakthroughs that happened in decentralized systems over these past two decades, and why they have failed to make meaningful inroads thus far: P2P networks, blockchains, and Data Storage Networks (DSNs).

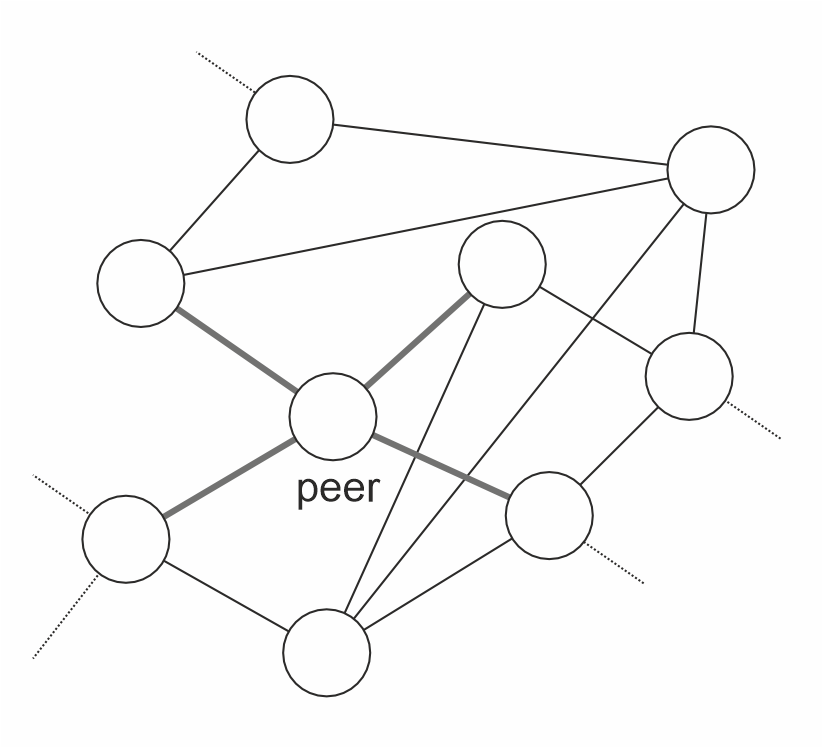

P2P Networks. P2P networks have been around for over two decades. Their premise is that users can run client software on their own machines and form a self-organizing network that enables sharing of resources like bandwidth, compute, and storage to provide higher-level services like search or decentralized file sharing without the need for a centralized controlling actor.

Early networks like BitTorrent[6], however, only had rudimentary incentives based on a form of barter economy in which nodes providing blocks to other nodes would be rewarded with access to more blocks. This provides some basic incentives for nodes to exchange the data they hold, but whether or not a node decides to hold a given piece of data is contingent on whether or not the node operator was interested in that data to begin with; i.e., a node will likely not download a movie if they are not interested in watching it.

Files which are not popular, therefore, tend to disappear from the network as no one is interested in them, and there is no way to incentivize nodes to do otherwise. This lack of even basic durability guarantees means BitTorrent and, in fact, most of the early p2p file-sharing networks, are suitable as distribution networks at best, but not as storage networks as data can, and probably will, be eventually lost. Even more recent attempts at decentralized file sharing like IPFS[7] suffer from similar shortcomings: by default, IPFS offers no durability guarantees, i.e., there is no way to punish a pinning service if it fails to keep data around.

Blockchains. Blockchains have been introduced as part of Bitcoin in 2008[8], with the next major player Ethereum[9] going live in 2013. A blockchain consists of a series of blocks, each containing a list of transactions. These blocks are linked together in chronological order through cryptographic hashes. Each block contains a hash of the previous block, which secures the chain against tampering. This structure ensures that once a block is added to the blockchain, the information it contains cannot be altered without redoing all subsequent blocks, making it secure against fraud and revisions. For all practical purposes, once a block gets added, it can no longer be removed.

This permanence allied to the fully replicated nature of blockchain means they provide very strong durability and availability guarantees, and this has been recognized since very early on. The full-replication model of blockchains, however, also turns out to be what makes them impractical for data storage: at the date of this writing, storing as little as a gigabyte of data on a chain like Ethereum remains prohibitively expensive[10].

Blockchains represent nevertheless a game-changing addition to decentralized systems in that they allow system designers to build much stronger and complex incentive mechanisms based on monetary economies, and to implement key mechanisms like cryptoeconomic security[11] through slashing, which were simply not possible before.

Decentralized Storage Networks (DSNs). Decentralized Storage Networks (DSNs) represent a natural stepping stone in decentralized storage: by combining traditional P2P technology with the strong incentive mechanisms afforded by modern blockchains and new cryptographic primitives, they provide a much more credible take on decentralized storage.

Like early P2P networks, DSNs consolidate storage capacities from various independent providers and orchestrate data storage and retrieval services for clients. Unlike early P2P networks, however, DSNs employ the much stronger mechanisms afforded by blockchains to incentivize correct operation. They typically employ remote auditing techniques like Zero-Knowledge proofs to hold participants accountable, coupled with staking/slashing mechanisms which inflict monetary losses on bad participants as they are caught.

In their seminal paper[12], the Filecoin team characterizes a DSN as a tuple

: Clients execute the Put protocol to store data under a unique identifier key. : Clients execute the Get protocol to retrieve data that is currently stored using key. : The network of participants coordinates via the Manage protocol to: control the available storage, audit the service offered by providers and repair possible faults. The Manage protocol is run by storage providers often in conjunction with clients or a network of auditors.

While useful, we argue this definition is incomplete as it pushes a number of key elements onto an unspecified black box protocol/primitive named

- incentive and slashing mechanisms;

- remote auditing and repair protocols;

- strategies for data redundancy and dispersal.

Such elements are of particular importance as one attempts to reason about what would be required to construct a DSN that provides actual utility. As we set out to design Codex and asked ourselves that question, we found that the key to useful DSNs is in durability; i.e., a storage system is only useful if it can provide durability guarantees that can be reasoned about.

In the next section, we explore a construct we name Decentralized Durability Engines which, we argue, lead to a more principled approach to designing storage systems that provide utility.

3. Decentralized Durability Engines (DDE)

A Decentralized Durability Engine is a tuple

is a set of redundancy mechanisms, such as erasure coding and replication, that ensure data availability and fault tolerance. is a set of remote auditing protocols that verify the integrity and availability of stored data. is a set of repair mechanisms that maintain the desired level of redundancy and data integrity by detecting and correcting data corruption and loss. is a set of incentive mechanisms that encourage nodes to behave honestly and reliably by rewarding good behavior and penalizing malicious or negligent actions. is a set of data dispersal algorithms that strategically distribute data fragments across multiple nodes to minimize the risk of data loss due to localized failures and to improve data availability and accessibility.

We argue that when designing a storage system that can keep data around, none of these elements are optional. Data needs to be redundant (

This is a somewhat informal treatment for now, but the actual parameters that would be input into any reliability analysis of a storage system would be contingent on those choices. In a future publication, we will explore how durability is affected by the choice of each of these elements in a formal framework.

4. Codex: A Decentralized Durability Engine

This section describes how Codex actually works. The primary motivation behind Codex is to provide a scalable and robust decentralized storage solution which addresses the limitations of existing DSNs. This includes: i) enhanced durability guarantees that can be reasoned about, ii) scalability and performance and iii) decentralization and censorship resistance.

We start this section by laying out key concepts required to understand how Codex works (Sec. 4.1). We then discuss the redundancy (

4.1. Concepts

In the context of Codex (and of storage systems in general), two properties appear as fundamental:

Availability. A system is said to be available when it is able to provide its intended service, and unavailable otherwise. The availability of a system over any given interval of time is given by [13]:

where

Durability. Quantified as a probability

If this number is very close to one, e.g.

Ideally, we would like storage systems to be highly available and highly durable. Since achieving provable availability is in general not possible[14], Codex focuses on stronger guarantees for durability and on incentivizing availability instead.

Dataset. A dataset

Storage Client (SC). A Storage Client is a node that participates in the Codex network to buy storage. These may be individuals seeking to backup the contents of their hard drives, or organizations seeking to store business data.

Storage Provider (SP). A Storage Provider is a node that participates in Codex by selling disk space to other nodes.

4.2. Overview

At a high level, storing data in Codex works as follows. Whenever a SC wishes to store a dataset

- splits

into disjoint partitions named slots, where each slot contains blocks; - erasure-codes

with a Reed-Solomon Code[15] by extending it into a new dataset which adds an extra parity blocks to (Sec. 4.3). This effectively adds new slots to the dataset. Since we use a systematic code, remains a prefix of ; - computes two different Merkle tree roots: one used for inclusion proofs during data exchange, based on SHA256, and another one for storage proofs, based on Poseidon2 (Sec 4.3);

- generates a content-addressable manifest for

and advertises it into the Codex DHT (Sec. 4.4); - posts a storage request containing a set of parameters in the Codex marketplace (on-chain), which includes things like how much the SC is willing to pay for storage, as well as expectations that may impact the profitability of candidate SPs and the durability guarantees for

, for each slot (Sec. 4.5).

The Codex marketplace (Sec. 4.5) then ensures that SPs willing to store data for a given storage request are provided a fair opportunity to do so. Eventually, for each slot

- declare its interest in it by filing a slot reservation;

- download the data for the slot from the SC;

- provide an initial proof of storage and some staking collateral for it.

Once this process completes, we say that slot

4.3. Erasure Coding, Repair, and Storage Proofs

Erasure coding plays two main roles in Codex: i) allowing data to be recovered following loss of one or more SPs and the slots that they hold (redundancy) and ii) enabling cost-effective proofs of storage. We will go through each of these aspects separately.

Erasure Coding for Redundancy. As described before, a dataset

Figure 1. A padded dataset

Codex then erasure-codes

Figure 2. Erasure-coded dataset

At each interleaving step, we collect

The Codex marketplace (Sec. 4.5) then employs mechanisms to ensure that each one of these slots are assigned to a different node so that failure probabilities for each slot are decorrelated. This is important as, bridging back to durability guarantees, assuming that we could know the probability

Erasure Coding for Storage Proofs. The other, less obvious way in which Codex employs erasure coding is locally at each SP when generating storage proofs. This allows Codex to be expedient in detecting both unintentional and malicious data loss with a high level of accuracy.

To understand how this works, imagine we had an SP that has promised to store some slot

A smarter approach would be by sampling: instead of downloading the entire file, the verifier can ask for a random subset of the blocks in the file and their Merkle inclusion proofs. While this also works, the problem here is that the probability of detecting lost blocks is directly impacted by what fraction of blocks

Although the decay is always geometric, the impact of having a loss fraction that is low (e.g. less than

Figure 3. Number of samples

The reason it is hard to detect loss is because we are attempting to find the perhaps single block that is missing out of

If we require SPs to locally encode slots with a code rate [16] that is higher than

The final step for Codex proofs is that they need to be publicly verifiable. The actual proving mechanism in Codex constructs a Groth16[18] proof so that it can be verified on-chain; i.e., the verifiers are the public blockchain nodes themselves. The implementation has therefore both an on-chain component, which contains the logic to determine when proofs are required and when they are overdue, and an off-chain component, which runs periodically to trigger those at the right instants.

Algorithm 1 depicts, in Python-pseudocode, the proving loop that SPs must run for every slot

It then asks the on-chain contract if a proof is required for this period (line frequency parameter (lines frequency blocks.

Going back to Algorithm 1, if a proof turns out to be required for the current period, the SP will then retrieve a random value from the contract (line

async def proving_loop(

dataset_root: Poseidon2Hash,

slot_root: Poseidon2Hash,

contract: StorageContract,

slot_index: int):

while True:

await contract.next_period()

if contract.is_proof_required():

randomness = contract.get_randomness()

merkle_proofs = compute_merkle_proofs(slot_root, randomness)

post(

zk_proof(

public = [randomness, dataset_root, slot_index],

private = [slot_root, merkle_proofs]

))Algorithm 1. Codex's proving loop (ran on SPs, off-chain).

It then uses this randomness to determine the indices of the blocks within the locally erasure-coded slot that it needs to provide proofs for, and computes Merkle inclusion proofs for each (line

def is_proof_required()

randomness = block.blockhash()

return randomness % frequency == 0:Algorithm 2. Checking if a proof is required (ran on smart contract, on-chain).

Merkle trees for proof verification are built using

Repair. The redundancy and proof mechanisms outlined so far allow Codex to repair data in a relatively simple fashion: missing proofs signal lost slots, and are used as failure detectors. Whenever a threshold amount of slots are lost, a lazy repair process is triggered in which the lost slots are put back on sale. Providers are then allowed to fill such slots again but, instead of downloading the slot itself, they download enough blocks from other nodes so they can reconstruct the missing slot, say,

The way Codex organizes its data as partitioned and erasure coded slots is largely inspired by HAIL[20]. The use of local erasure coding and compact proofs is instead inspired by earlier work on PoRs[21] and PDPs[22], as well as compact PoRs[23].

A key aspect of the Codex proving system is that it attempts to be as lightweight as possible. The final goal is to be able to run it on simple computers equipped with inexpensive CPUs and modest amounts of RAM. Current requirements for home SPs are well around what a NUC or consumer laptop can provide, but those should drop even further as we optimize it. This is key as an efficient proving system means that:

- both non-storage hardware; e.g. CPUs and RAM, and electricity overhead costs for proofs should be small. This leads to better margins for SPs;

- minimal requirements are modest, which favours decentralization.

4.4. Publishing and Retrieving Data

Datasets stored in Codex need to be advertised over a Distributed Hash Table (DHT), which is a flavour of the Kademlia DHT[24], so they can be located and retrieved by other peers. At a basic level, the Codex DHT maps Content IDentifiers (CIDs)[25], which identify data, onto provider lists, which identify peers holding that data.

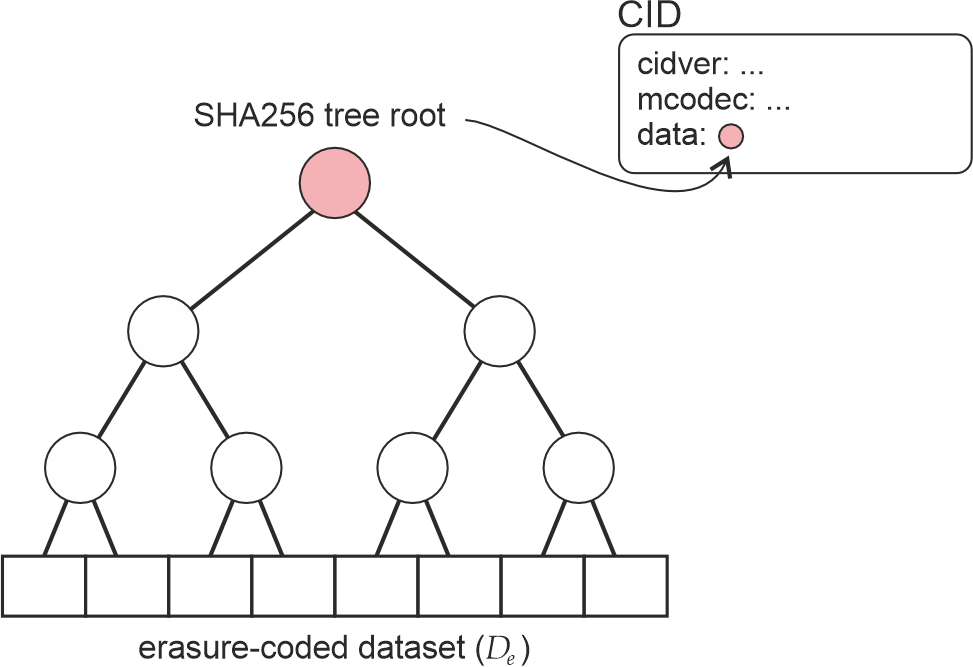

A CID unequivocally identifies a piece of data by encoding a flavour of a hash of its content together with the type of hashing method used to compute it. In the case of a Codex dataset

Figure 4. CIDs for Codex datasets.

Nodes that hold either part or the entirety of

This structure affords a great deal of flexibility in how peers choose to communicate and encode datasets, and is key in creating a p2p network which can support multiple concurrent p2p client versions and can therefore be upgraded seamlessly.

Metadata. Codex stores dataset metadata in descriptors called manifests. Those are currently kept separate from the dataset itself, in a manner similar to BitTorrent's torrent files. They contain metadata on a number of attributes required to describe and properly process the dataset, such as the Merkle roots for both the content (SHA256) and proof (

Manifests are currently stored as content-addressable blocks in Codex and treated similarly to datasets: nodes holding the manifest of a given dataset will advertise its CID onto the DHT, which is computed by taking a SHA256 hash of the manifest's contents. Since manifests are stored separate from the dataset, however, they can also be exchanged out-of-band, like torrent files can.

Other systems choose tighter coupling between the metadata and the dataset. IPFS and Swarm use cryptographic structures such as Merkle DAG and a Merkle Tree, where intermediate nodes are placed on the network and queried iteratively to retrieve the respective vertexes and leaves. Such design decisions have their own tradeoffs and advantages, for example an advantage of storing the metadata in a single addressable unit is that it eliminates intermediary network round trips, as opposed to a distributed cryptographic structure such as a tree or a DAG.

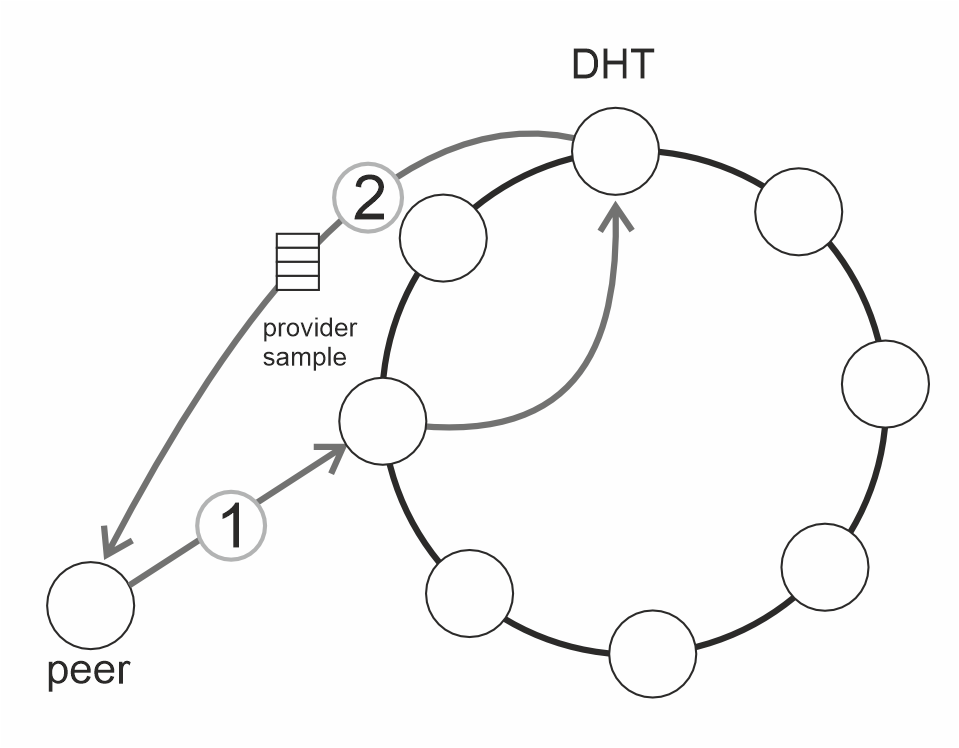

Retrieving data. Data retrieval in Codex follows a process similar to BitTorrent: a peer wishing to download a dataset

(a)

(b)

Figure 5. (a) DHT lookup and (b) download swarm.

The nodes responsible for that CID will reply with a (randomized) subset of the providers for that CID (Figure 5a (2)). The peer can then contact these nodes to bootstrap itself into a download swarm (Figure 5b). Once part of the swarm, the peer will engage in an exchange protocol similar to BitSwap[28] by advertising the blocks it wishes to download to neighbors, and receiving requests from neighbors in return. Dropped peers are replaced by querying the DHT again. Note that SPs always participate in the swarms for the datasets they host, acting as seeders. Since the mechanism is so similar to BitTorrent, we expect Codex to scale at least as well.

Codex right now relies on simple incentive mechanisms to ensure that peers share blocks. There is current ongoing work on bandwidth incentives and, in future versions, peers will be able to purchase block transfers from each other.

4.5. Codex Marketplace

The Codex marketplace is the set of components that run both on-chain, as smart contracts, and off-chain, as part of both SCs and SPs. Its main goal is to define and enforce the set of rules which together enable: i) orderly selling and purchasing of storage; ii) verification of storage proofs; iii) rules for penalizing faulty actors (slashing) and compensating SP repairs and SC data loss; and iv) various other aspects of the system's economics, which will be discussed as part of an upcoming Codex tokenomics litepaper.

Codex implements an ask/bid market in which SCs post storage requests on chain, and SPs can then act on those if they turn out to be profitable. This means that the request side; i.e., how much an SC is willing to pay, is always visible, whereas the bid side; i.e., at what price an SP is willing to sell, is not.

An SC that wishes Codex to store a dataset

- Size in bytes. Specifies how many storage bytes the SC wishes to purchase.

- Duration. Specifies for how long the SC wishes to purchase the storage bytes in (1); e.g. one year.

- Number of slots. Contains the number of slots in

. This is derived from the erasure coding parameters and discussed in Sec. 4.3. - Price. The price this SC is willing to pay for storage, expressed as a fractional amount of Codex tokens per byte, per second. For instance, if this is set to

and the SC wants to buy of storage for seconds, then this means the SC is willing to disburse million Codex tokens for this request. - Collateral per slot. Dictates the amount of Codex tokens that the SP is expected to put as collateral if they decide to fulfill a slot in this request (staking). Failure to provide timely proofs may result in loss of this collateral (slashing).

As discussed in Sec. 5, these parameters may impact durability guarantees directly, and the system offers complete flexibility so that applications can tailor spending and parameters to specific needs. Applications built on Codex will need to provide guidance to their users so they can pick the correct parameters for their needs, not unlike Ethereum wallets help users determine gas fees.

Figure 6. Storage requests and their processing by SPs.

As depicted in Figure 6, every storage request posted by an SC gets recorded on-chain, and generates a blockchain event that SPs listen to. Internally, SPs will rank unfilled storage requests by their own criteria, typically profitability, and will attempt to fill the slots for requests that are most interesting to them first. As discussed in Sec. 4.2, filling a slot entails: i) reserving the slot on-chain; ii) downloading the data from the SC; iii) providing an initial storage proof as well as the staking collateral.

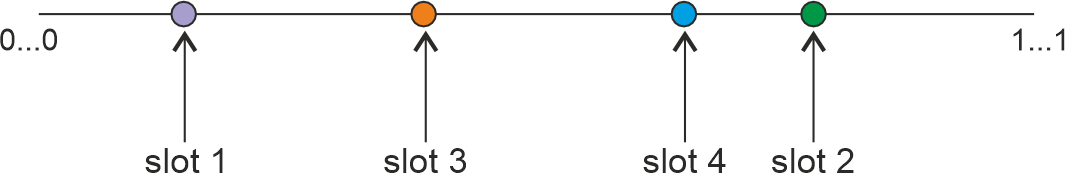

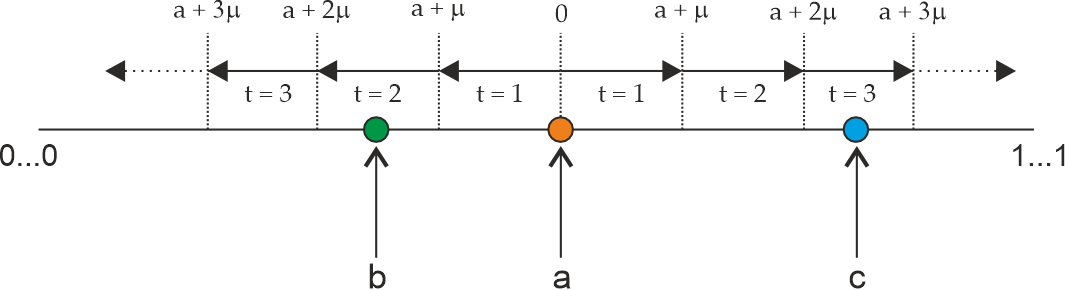

Ensuring diversity. SPs compete for unfilled slots. If we allowed this competition to happen purely based on latency; i.e., the fastest provider to reserve a slot wins, we could easily end up with a system that is too centralized or, even worse, with multiple slots ending up at a single provider. The latter is particularly serious as failures within a provider may not be decorrelated, and we therefore want to ensure that the distribution of slots amongst providers is as randomized as possible.

To help mitigate these issues, the Codex marketplace implements a time-based, expanding window mechanism to allow SPs to compete for slots. As depicted in Figure 7, each storage request is assigned a random position in a

Figure 7. Slots placed at random in a

We then allow only hosts whose blockchain IDs are within a certain "distance" of a slot to compete in filling it (Figure 8).

Figure 8. SP eligibility as a function of time and its distance to a slot.

This distance expands over time according to a dispersal parameter

where

5. Reliability Analysis

In this section, we provide an initial analysis of durability for Codex. The main goal is investigating the values for

Codex, as a system, stores a large amount of datasets, each encoded, distributed, verified, and repaired according to the specific parameters set up in the respective storage contract. Since datasets are set up independently and operate (mostly) independently, we can model the system at the level of the dataset. We will later discuss correlation between various datasets stored in the system.

In our first model, we use a Continuous Time Markov-Chain (CTMC) model to describe the state of the dataset at any time instance. The model considers the following aspects of Codex:

- dataset encoding;

- node failures;

- the proving process;

- dataset repair.

Before discussing the state space and the rate matix of the CTMC model, lets describe these aspects of the system.

As before, we assume a dataset

5.1. Failure Model

When discussing failures, we should differentiate between transient and permanent failures, as well as between catastrophic node failures (the slot data is entirely lost) and partial failures.

In our first model, we focus on permanent node failures. From the perspective of Codex, a node is considered lost if it cannot provide proofs. Permanent node failure can be due to disk failure, to other hardware or software failures leading to data corruption, but also due to operational risks, including hardware failures, network failures, or operational decisions.

Unrepairable hardware failures are typically characterized with their MTTF (Mean Time To Failure) metric, assuming an exponential distribution of the time to failure. There are various MTTF statistics available about disk failures[29].

As a first approximation, one could start from the above disk MTTF numbers, and try to factor in other reasons of permanent node failures. Disk MTTF is specified in the range of 1e+6 hours, however, we have good reasons to be more pessimistic, or at least err on the more unreliable side, and assume MTTF in the 1e+4 hour range, i.e. around a year.

For the sake of modeling, we also assume i.i.d. (independent and identically distributed) failures among the set of nodes storing a given dataset. This is an optimistic model compared to cases where some storage providers might fail together e.g. because of being on shared hardware, in the same data center, or being under the same administrative authority. We will model these correlated events in a separate document.

There might also be malicious nodes in the set of storage providers, e.g. withholding data when reconstruction would be required. Again, we will extend the model to these in a separate document.

5.2. Reconstruction Model

The next important time related parameter of the model is MTTR (Mean Time To Reconstruct). While we model events at the level of a single dataset, it is important to note here that a failure event most probably involves entire disks or entire nodes with multiple disks, with many datasets and a large amount of data. Therefore, in the case of reconstruction, the stochastic processes of individual datasets are not independent of each other, leading to higher and uncertain reconstruction times.

The actual repair time depends on a number of factors:

- time to start repairing the dataset,

- data transmission for the purposes of Erasure Code decoding,

- EC decoding itself,

- allocating the new nodes to hold the repaired blocks,

- distributing repaired data to the allocated nodes.

Overall, it is clearly not easy to come up with a reasonable distribution for the time of repair, not even the mean time of repair. While time to repair is most probably not an exponential distribution, we model it as such in a first approximation to allow Markov Chain based modeling.

5.3. Triggering Reconstruction

Reconstruction and re-allocation of slots can be triggered by the observed state, and our system "observes" state through the proving process. In our model, we assume that nodes are providing proofs according to a random process with an exponential distribution between proving times, with MTBF (Mean Time Between Proofs) mean, i.i.d. between nodes. Other distributions are also possible, but for the sake of modelling we start with an exponential distribution, which is also simple to implement in practice.

Reconstruction can be triggered based on the observed state in various ways:

- if an individual node is missing a slot proof (or more generally, a series of proofs), reconstruction can start. The advantage of this option is that the consequences of failing a proof only depend on the node itself, and not on other nodes.

- reconstruction can also be triggered by the observed system state, i.e. the number of nodes that have missed the last proof (or more in general some of the last proofs). In fact, thanks to the properties of RS codes, whenever a slot is being repaired, all slot's data are regenerated. As a consequence, the cost of repair is independent of the number of slots being repaired, and by triggering repair only after multiple slots are observed lost (the so called "lazy repair"), we can drastically reduce the cost of repair.

In our model, we assume reconstruction that uses a combination of the above two triggers.

- Reconstruction is triggered based on the observed system state, allowing for lazy repair, by triggering it when

of the slots is considered lost. - A single slot is considered lost if it was missing the last

proofs.

Other reconstruction strategies, such as considering all the proofs from all the slots in a time window, are also possible, but we leave these for further study.

5.4. CTMC Model

We model the system using a CTMC with a multi-dimensional state space representing slot status and proof progress. To keep the description simple, we introduce the model for the case of

State space. We model the system with a multi-dimensional state space

- losses:

: the number of lost slots. Practical values of go from to . As soon as reaches , the dataset can be considered lost. - observations:

is the number of slots with the last test failed, or in other words, observed losses. Repair is triggered when . Since repair reallocates slots to new nodes, we can assume that repaired slots are all available after the process. Hence, in all reachable states.

State transition rates. From a given state

- slot loss,

: slot loss is driven by MTTF, assuming i.i.d slot losses. Obviously, only available slots can be lost, so the transition probability also depends on . - missing proofs,

: we are only interested in the event of observing the loss of a slot that we haven't seen before. Thus, the state transition probability depends on . - repair,

: repair is only triggered once the number of observed losses reaches the lazy repair threshold . In case of a successful repair, all slots are fully restored (even if the actual set of nodes storing the slots are changing).

States

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows dataset reliability (

The figure also shows what

Table 1. Expansion, lazy repair, and required values for

5.5 Proving frequency

An important parameter to asses is the frequency of proofs, expressed in our model as MTBP, since it directly translates into proof generation and proof submission costs. If we could double MTBP, we could halve the associated costs.

Figure 10.

In Figure 10 we keep MTTF 1 year and MTTR 1 day, like before, and we show

As expected, large values of MTBP (infrequent proofs) are not acceptable, the dataset could easily be lost without triggering repair. What the curves also show is that requiring proofs with an MTBF below a day does not make a significant difference. In fact, with several parameter combinations, namely, with higher

Note however that we are still using

6. Conclusions and Future Work

We have presented Codex, a Decentralized Durability Engine which employs erasure coding and efficient proofs of storage to provide tunable durability guarantees and a favourable tradeoff in cost and complexity for storage providers. By having proofs that are lightweight, Codex can keep the overhead spendings on hardware and electricity to a minimal. This is important both for fostering participation, as storage provider margins can be increased while prices for clients can decrease, and decentralization, as modest requirements are more likely to encourage a more diverse set of participants ranging from hobbyist home providers to larger players.

Despite our ambitious goals, Codex is a work in progress. Ongoing efforts on improving it include:

- Reduction of proving costs. Verifying proofs on-chain is expensive. To bring down costs on the short-term, we are working on an in-node aggregation mechanism which allow providers to batch proofs over multiple slots. On a slightly longer time horizon, we also intend to build our own aggregation network, which will ultimately allow Codex to go on-chain very infrequentely. Finally, at the level of individual proofs, we are working on more efficient proof systems which should bring down hardware requirements even more.

- Bandwidth incentives. Codex is designed to provide strong incentives that favor durability. While incentivizing availability is harder as it is in general not possible to provide proofs for it[14:1] we can still provide an effective, even if weaker, form of incentive by allowing providers to sell bandwidth. To that end, we are currently working on mechanisms to enable an efficient bandwidth market in Codex which should complement the storage market.

- Privacy and encryption. Codex will, in the future, encrypt data by default so that SPs cannot ever know what they are storing. This should also offer SCs more privacy.

- P2P layer. We are currently working on optimizing protocols so they scale and perform better. This includes improvements in block transfer latency and throughput, more efficient swarms and block discovery mechanism, as well as research into more secure protocols.

- Tools and APIs. We are currently working on creating developer tools (SDKs) and APIs to facilitate the development of decentralized applications on top of the Codex network.

Work within a longer time horizon include:

- Support for fine-grained and mutable files. Codex, as many other DSNs, is currently suitable for large immutable datasets, and any other use case will currently require additional middleware. We have ongoing work on exploring polynomial commitments as opposed to Merkle trees for proofs, which should allow us to incrementally change datasets without having to completely re-encode them. This will unlock a host of new use cases, and allow Codex to be used in a much more natural fashion.

- Improvements to erasure coding. There is a large number of different codes offering different tradeoffs, e.g. non-MDS codes like turbocodes and tornado codes, which could result in better performance than the Reed-Solomon codes we currently employ.

Codex has the potential to support a wide range of use cases, from personal data storage and decentralized web hosting to secure data backup and archival, decentralized identities, and decentralized content distribution.

Ultimately, the use case for Codex is that of a durable and functional decentralized storage layer, without which no decentralized technology stack can be seriously contemplated. As the decentralized ecosystem continues to evolve, we expect Codex’s DDE-based approach to storage to play a crucial role in enabling new types of applications and services that prioritize user control, privacy, and resilience.

References

Zippia. "25 Amazing Cloud Adoption Statistics [2023]: Cloud Migration, Computing, And More" Zippia.com. Jun. 22, 2023, https://www.zippia.com/advice/cloud-adoption-statistics/ ↩︎

D. Brown, J. Smith, and A. Johnson, "Beyond eleven nines: Lessons from the Amazon S3 culture of durability," presented at AWS re:Invent 2019, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://d1.awsstatic.com/events/reinvent/2019/REPEAT_1_Beyond_eleven_nines_Lessons_from_the_Amazon_S3_culture_of_durability_STG331-R1.pdf. [Accessed: Aug. 29, 2024]. ↩︎

J. Liu, "Government Backdoor in Cloud Services: Ethics of Data Security," USC Viterbi Conversations in Ethics, vol. 3, no. 2, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://vce.usc.edu/volume-3-issue-2/government-backdoor-in-cloud-services-ethics-of-data-security/. [Accessed: Aug. 27, 2024]. ↩︎

DigitalOcean, "The Business Benefits of a Multi-Cloud Strategy," [Online]. Available: https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/the-business-benefits-of-a-multi-cloud-strategy. [Accessed: Aug. 27, 2024]. ↩︎

Y. Feng, B. Li and B. Li, "Price Competition in an Oligopoly Market with Multiple IaaS Cloud Providers" in IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. 63, no. 01, pp. 59-73, 2014. ↩︎

B. Cohen, "BitTorrent - a new P2P app," Yahoo! Groups - decentralization, Jul. 2, 2001. [Online]. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20080129085545/http://finance.groups.yahoo.com/group/decentralization/message/3160 [Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024] ↩︎

IPFS: An open system to manage data without a central server," IPFS, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ipfs.tech/. [Accessed: Sep. 28, 2024]. ↩︎

S. Nakamoto, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System," 2008. [Online]. Available: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf ↩︎

V. Buterin, "Ethereum White Paper: A Next Generation Smart Contract & Decentralized Application Platform," 2013. [Online]. Available: https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper/ ↩︎

P. Kostamis, A. Sendros, and P. S. Efraimidis, "Data management in Ethereum DApps: A cost and performance analysis," Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 145, pp. 193-205, Apr. 2024. ↩︎

A. Chaudhry, S. Kannan and D. Tse, "STAKESURE: Proof of Stake Mechanisms with Strong Cryptoeconomic Safety," arXiv:2401.05797 [cs.CR], Jan. 2024. ↩︎

Protocol Labs, "Filecoin: A Decentralized Storage Network," Jul. 19, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://filecoin.io/filecoin.pdf ↩︎

A. S. Tanenbaum and M. van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson Education, 2007. ↩︎

M. Al-Bassam, A. Sonnino, and V. Buterin, "Fraud and Data Availability Proofs: Maximising Light Client Security and Scaling Blockchains with Dishonest Majorities," arXiv:1809.09044 [cs.CR], May 2019 ↩︎ ↩︎

I. S. Reed and G. Solomon, "Polynomial Codes Over Certain Finite Fields," Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 300-304, 1960 ↩︎

"Code rate," Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_rate (accessed Sep. 26, 2024). ↩︎

M. Spanbroek, "Storage Proofs & Erasure Coding," https://github.com/codex-storage/codex-research/blob/master/design/proof-erasure-coding.md (accessed Sep. 26, 2024). ↩︎

J. Groth, "On the Size of Pairing-based Non-interactive Arguments," in Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2016, M. Fischlin and J.-S. Coron, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016, pp. 305-326. ↩︎

L. Grassi, D. Khovratovich, and M. Schofnegger, "Poseidon2: A Faster Version of the Poseidon Hash Function," Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2023/323, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/323 ↩︎

K. D. Bowers, A. Juels, and A. Oprea, "HAIL: A high-availability and integrity layer for cloud storage," in Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS '09), Chicago, Illinois, USA, Nov. 2009, pp. 187-198. ↩︎

A. Juels et al., "Pors: proofs of retrievability for large files," in Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS '07), Alexandria, Virginia, USA, Oct. 2007, pp. 584-597 ↩︎

G. Ateniese et al., "Provable data possession at untrusted stores," in Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS '07), Alexandria, Virginia, USA, Oct. 2007, pp. 598-609. ↩︎

H. Shacham and B. Waters, "Compact Proofs of Retrievability," in Advances in Cryptology - ASIACRYPT 2008, J. Pieprzyk, Ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 90-107. ↩︎

P. Maymounkov and D. Mazieres, "Kademlia: A peer-to-peer information system based on the XOR metric," in Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Peer-to-Peer Systems (IPTPS), Cambridge, MA, USA, Mar. 2002, pp. 53-65. ↩︎

Protocol Labs. "CID (Content IDentifier) Specification," https://github.com/multiformats/cid (accessed Sep. 26, 2024) ↩︎

libp2p. "RPC 0003 - Routing Records," https://github.com/libp2p/specs/blob/master/RFC/0003-routing-records.md (accessed Sep. 26, 2024) ↩︎

Protocol Labs. "Multiformats / Multiaddr," https://multiformats.io/multiaddr/ (accessed Sep. 26, 2024) ↩︎

IPFS Standards. "Bitswap Protocol," https://specs.ipfs.tech/bitswap-protocol/ (accessed Sep. 27, 2024) ↩︎

B. Schroeder and G. A. Gibson, "Disk Failures in the Real World: What Does an MTTF of 1,000,000 Hours Mean to You?," in Proceedings of the 5th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST '07), San Jose, CA, USA, 2007 ↩︎